Adventure Montessori

A unique and enriching experience tailored to your child's needs!

Welcome to Adventure Montessori

For years, Adventure Montessori has provided top-quality early childhood education for children from infants through sixth grade. We offer a safe and nurturing educational environment in a Montessori setting. We believe, in our Montessori environment, that every child will become competent, confident, compassionate, and above all capable. We know that within each child is the seed of unlimited potential which will guide that child into adulthood. We are a private school, where we emphasize an individualized educational experience, as opposed to a strict “one size, fits all” based education.

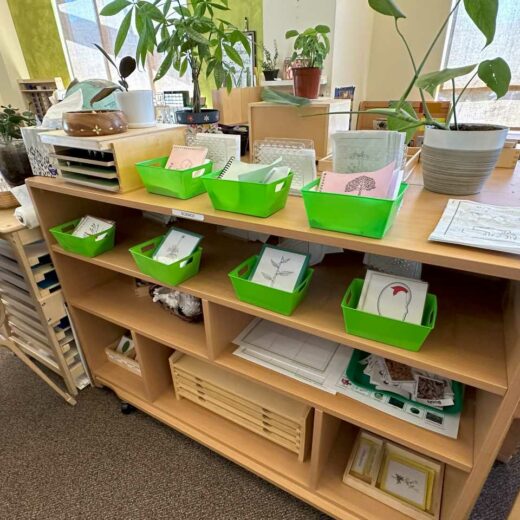

Our Programs

Growing for the future

At Adventure Montessori, we want to set your children in the right direction! That’s why our Montessori-focused center is designed to provide quality education that prepares them for continued growth and success.

We Are Hiring!

At Adventure Montessori, our staff is at the heart of everything we do! We’re looking for fun, caring, and vibrant individuals who are passionate about early-childhood education to join our team.